Mitchell FC #8

SOLD

Item #C10641

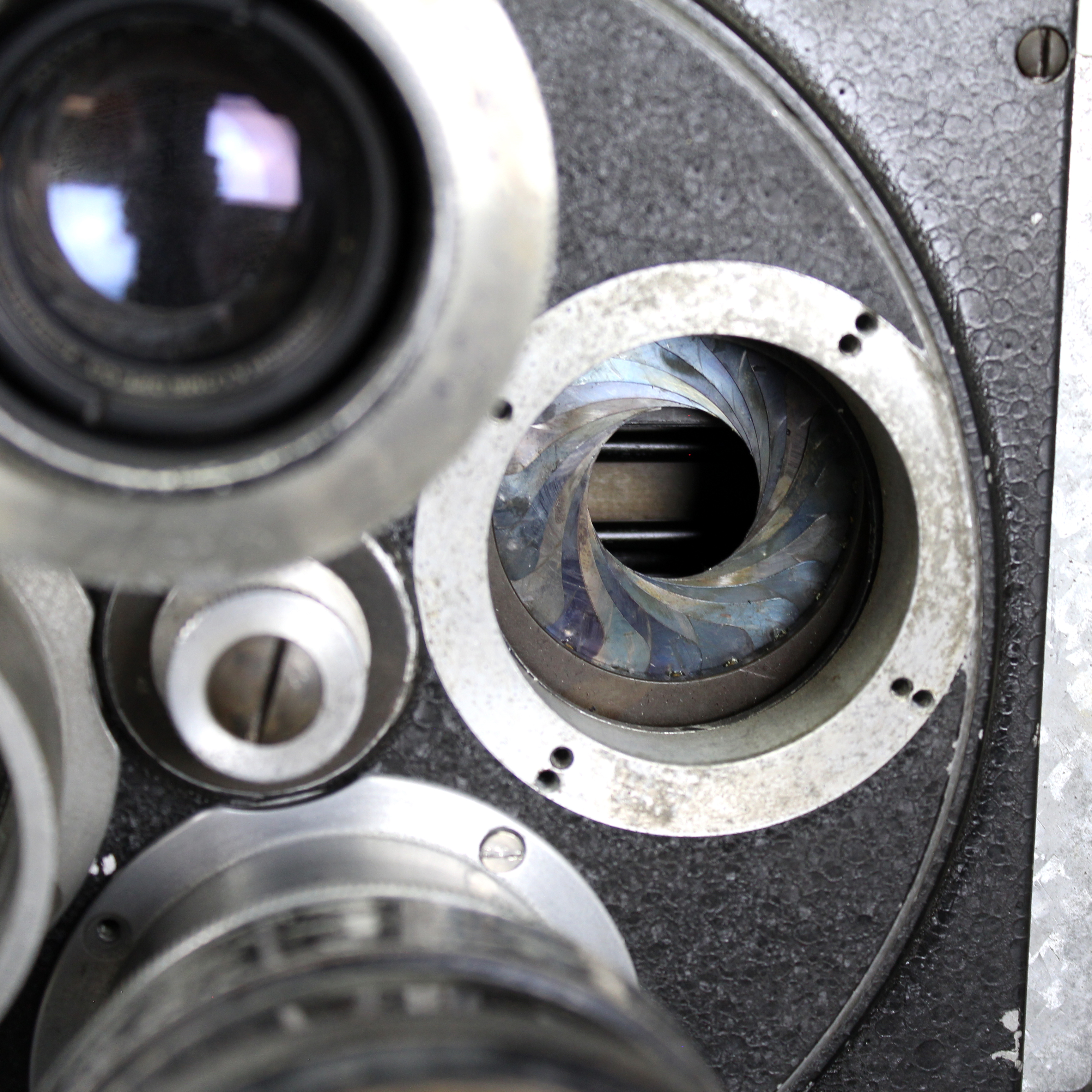

Like other top-of-the-line Mitchell production cameras, Mitchell FC #8 includes the iconic Mitchell rackover L-base, a 4 position rotating lens turret, a variable shutter with auto fade, a built-in adjustable iris, right/left and top/bottom adjustable effects mattes, and a behind-the-lens combination filter and effects wheel. The camera is paired with its original matching serialized matte box, 2 Grandeur format lenses, a 1000’ 70mm magazine, a later Mitchell BFC sidefinder, a Mitchell FC pan/tilt friction head, and a period Mitchell wooden tripod. We have conducted extensive research into the history of this camera, and believe that it was one of the 8 Grandeur cameras that worked on Raoul Walsh’s 1930 film, “The Big Trail” which starred a young John Wayne in his first leading role. Mitchell FC (“Fox Camera”) #8 was originally purchased by the Fox Film Corporation in 19291. The Fox Film Corporation was established in February 1915 by William Fox in New York City, and remained a major producer of motion pictures on both the east and west coasts until the company merged with Twentieth Century Pictures in 1935. William Fox himself was at the helm of his company, maintaining control of the company’s productions until 1930 when he was ousted in a hostile takeover. Mitchell FC cameras were specially designed for William Fox to shoot the 70mm Grandeur wide film system that Fox was developing in the late 1920’s. In basic design, the Mitchell FC is a Mitchell Standard that has been enlarged to accommodate 70mm film.

The Origin of Grandeur

The motion picture industry was in a period of transition in the late 1920s. Sound films were set to remake the previously silent industry, changing everything about how movies were made and exhibited. As the popularity of movies rose, bigger theaters were built to accommodate the ever-increasing audiences. The Roxy Theater in New York, which opened its doors in 1927, could seat more than 6,000 people in its massive auditorium2. Bigger theaters called for bigger screens, but the 35mm film of the day could only be magnified to a certain point before the grain became too obtrusive. Additionally, experiments into early television transmission made movie industry leaders nervous about the future of their theaters. William Fox, head of the Fox Film Corporation, sought a solution to these problems by developing a system that would project higher fidelity images on larger screens.

Previously, Fox had attempted to corner the sound-on-film market by purchasing the Movietone sound-on-film system from developers Theodore Case and Earl Sponable3. He had also acquired the American rights to the German Tri-Ergon patents, an essential part of the contemporary sound systems4. In a similar strategy, Fox hoped to develop a widescreen format that he could license to the rest of the industry. To this end, Fox hired Sponable to be his head of research and development at the newly established Fox Case Corporation. Sponable continued in this post from 1926 until he retired in 19625.

Camera Development Begins

In August 1927, Courtland Smith, manager of the Fox Case Corporation and Vice President in charge of Newsreels, was approached by William Waddell and John D. Elms to arrange a demonstration of Elms’ Widescope camera system6. Developed by Mr. Elms in 1922, the initial version of the Widescope camera used two divergent lenses set at right angles to two strips of 35mm film and focused both lenses simultaneously7. When exhibited, two projectors were linked together to project both strips of film at the same time, thus creating a widescreen image. Sponable found this system impractical, but Fox and Smith were impressed enough to license the system from Elms and hire him to work in their facility to further develop his camera8. Elms began work on the second iteration of his Widescope camera, which was to include a sound-on-film system, in September 1927 at the job shop of Stoeger & Company in New York9. This version of the camera used a “revolving lens” that photographed an image on a curved film plane. Elms patented this design that December and the system was tested in February 192810. Correspondence indicates that the Elms “revolving lens” Grandeur camera and a Mitchell camera were sent to photograph a short subject at Niagara Falls in August 192811. It seems likely that this short subject was one of the items shown at the first Grandeur presentation12. A third and final version of Elms’ camera was begun in October 1928 at the J.M. Wall Machine Company, with Elms’ son Charles in the lead13. This camera also employed a “revolving lens”, and work on the camera continued through August 1929, when it was abandoned14.

Sponable did not find any of the Widescope designs commercially viable, and so began his own work on a “regular news camera for Grandeur film” in January 192815. This camera was successfully completed in the shop of the J.M. Wall Machine Company in early February 192916. At the same time, the Mitchell Camera Corporation was contracted in February 1928 to modify a Mitchell Standard to accommodate 70mm Grandeur film. The camera was completed that August and tests made with it were a success. This camera, known as the Mitchell FC, or Fox Camera, would become the main wide film camera the Fox Film Corporation would use to produce their Grandeur films.

Evidence from memos and correspondence from Sponable, Smith, Fox, and others involved in the Grandeur project suggest that the first Widescope “revolving lens” camera was used to film a short subject of Niagara Falls in August 192817. An inventory of Grandeur equipment conducted in November 1929 indicates that two single system Grandeur cameras were on order from Wall. Two Grandeur sound cameras had been completed and one was currently in use on the Benjamin Stoloff production “Happy Days”18. These cameras, we believe, were among those built by the J.M. Wall Machine Company. Additionally, invoices show that three Mitchell FC cameras were ordered in December 1928, and ten more in June 192919. Advertising from Mitchell in “American Cinematographer” indicates that their FC cameras were used to film all four Fox Grandeur features, “Fox Movietone Follies of 1929”, “Happy Days”, “Song O’ My Heart”, and “The Big Trail”20.

Grandeur Makes Its Debut

The first public demonstration of Grandeur occurred on September 17, 1929 at the Gaiety Theater in New York City. On the program that night was a short featuring scenes from Niagara Falls, a Grandeur Movietone Newsreel, and a special Grandeur version of “Fox Movietone Follies of 1929.” Advertising for the special two week run proclaimed, “Grandeur does for vision what Fox Movietone does for sound”21. Critics and audiences were impressed by the outdoor scenes shown in the short and newsreel, but less so by “Follies.” A piece in the New York times following the premiere raved about the massive screen size, the high quality of the sound, and the illusion of depth created by the Grandeur format22. “Fox Movietone Follies of 1929” was released during a time when musical reviews were all the rage, and it was popular enough to spawn a sequel of sorts, “Fox Movietone Follies of 1930” the following year. Directed by David Butler and Marcel Silver (who directed the revue sequences), the 35mm version of the “Fox Movietone Follies of 1929" was widely distributed and popular with audiences of the time. Unfortunately, there are currently no known copies of either the 35mm or 70mm versions and the film is considered lost.

While the Grandeur version of “Follies” was more a proof of concept, and only exhibited for a single run at the Gaiety Theater, the second of Fox’s Grandeur features premiered on both coasts. The movie in question was “Happy Days,” another musical review of sorts, directed by Benjamin Stoloff and photographed in Grandeur by J.O. Taylor. It premiered at the Roxy Theater in New York in February 193023. Prior to the show, teams spent six weeks installing new projection equipment and a massive 42 ft x 20 ft screen24. A second premiere was held in Los Angeles at the Carthay Circle Theater25. Critics and audiences were impressed with the wide views provided by the Grandeur process, Los Angeles Times critic Edwin Schallert noting, "I do not know of anything that has afforded a more spectacular thrill in a long time than the glimpse of a train running along a winding stretch of river... which gives the first full inkling of the marvelous possibilities of a new and much heralded development"26. “Happy Days” featured all of the current Fox favorites, such as Janet Gaynor, Charles Farrell, and Victor McLagen, and marked the film debut of Betty Grable27. Following premiere night in Los Angeles, noted showman Sid Grauman was quoted as saying, "It is an overwhelming success. . . At the end of the intermission at the Carthay Circle I noticed that half a dozen famous producers left the theater and did not come back. I saw them a few minutes later in Beverly Hills sending telegrams to all parts of the United States regarding Grandeur film. Grandeur will revolutionize studio and exhibition methods from the ground up"28.

One of the key features of the Grandeur system was the size of its Movietone soundtrack. It almost tripled the soundtrack area from 2mm on standard 35mm film to 7mm on Grandeur 70mm film29. This was to be used to full effect for the third Fox Grandeur musical feature, “Song O’ My Heart,” starring famed Irish tenor John McCormack. Winfield Sheehan, vice president of production at Fox, had been trying for months to get McCormack to sign a contract to make a movie for the studio. Sheehan finally succeeded in May 1929 when McCormack signed a $500,000 contract to star in a still untitled film30. “Song O’ My Heart” was filmed in both Grandeur and 35mm in Ireland and Los Angeles, with McCormack performing a total of 12 songs31. While evidence suggests that the film was completed in both 35mm and 70mm versions, there is no mention that we have found of the Grandeur version having ever been screened. In fact, despite opening to great critical acclaim at the 44th Street Theatre in New York on March 11, 1930, the film was considered lost until the 1970’s when a version was discovered in the Fox vaults by Miles Kreuger32. The 70mm version is believed to have been destroyed in a Fox vault fire in the late 1930’s. The 35mm restoration was released in a DVD boxed set titled “Murnau, Borzage and Fox” in 2008.

The Final Feature

Raoul Walsh’s “The Big Trail” was the final Grandeur feature for Fox during this initial foray into widescreen cinema. Notably, it would be Twentieth Century Fox and Earl Sponable who were responsible for the next big widescreen push in the 1950’s when they developed the CinemaScope anamorphic system. “The Big Trail” was notable at the time, not only for being shot in Grandeur, but also for being a sound feature shot entirely outdoors, as well as the 7-state location tour the production took to make the film. Director Raoul Walsh, whose previous hits included “What Price Glory” (1926) and “The Thief of Baghdad” (1924), was at the helm of this massive undertaking. Arthur Edeson, known for his recent work on the Fox Movietone feature “In Old Arizona” (1928), the first sound film shot entirely outdoors, headed the team of Grandeur cameramen working on "The Big Trail". In all, eight Grandeur cameramen are credited on the film, as well as six standard format cameramen, led by veteran cinematographer Lucien Androit. Famed Fox Studio still photographer Frank Powolny, best known for his 1943 pin-up shot of Betty Grable and his many photographs of Marilyn Monroe, was the official still cameraman33. “The Big Trail” tells an epic tale of pioneers journeying west along the Oregon Trail in the 1830s. The production traveled more than 4,300 miles and included a fleet of 200 covered wagons, 1,800 head of cattle, 1,400 horses, 80 oxen, 110 mules, 200 chickens, 20 pigs and 14 dogs, along with a traveling cast of some 347 players. Five Native American tribes appeared in the film, and a total of 1,300,000 feet of film were reportedly shot, approximately 700,000 feet of Grandeur film and 500,000 feet of 35mm film34.

There are 14 cameramen listed in the credits for “The Big Trail”, eight Grandeur cameramen and six 35mm cameramen. Contemporary articles and still photo captions claim that as many as 46 cameras were used on the whole production, in both 35mm and 70mm formats35. One such photograph indicates that Walsh "had a battery of cameras located at eight different points shooting the fording of the river scene"36. The cast and crew traveled far and wide during the 5 months of principle photography, beginning in the desserts of Yuma, Arizona where they filmed the initial scenes of the wagon train as they first set out on their journey. A massive set was constructed in the Yuma dessert, the largest outdoor set ever built at that time, to recreate the river town where the wagon train began its journey37. Production traveled through the Grand Canyon in Arizona, through the town of St. George, Utah and on into Zion National Park. Cabins had to be built to house cast and crew during their six week stay in Moran, Wyoming, a small town just outside of Grand Teton National Park38. They filmed a buffalo hunt scene in northern Montana near the town of Moiese at the National Buffalo Range. Additional scenes were filmed in Oregon, Idaho, and California, including a river fording sequence in Sacramento, California, and the film’s finale among the massive trees of Sequoia National Park. Special trains carried the cast and crew to most of their locations, utilizing eight different train lines, and with more than 100 baggage cars to carry their equipment39.

Hailed as "the most important picture ever produced" 40 on studio advertisements, there were high hopes for this film that starred a very young John Wayne in his first leading role. More than two million dollars were spent on production, all for a feature that was to be carried by a young, unknown, and untried star. Additionally, “The Big Trail” was shot in six different versions, including the Grandeur and 35mm versions in English, as well as 35mm versions in Spanish, French, German, and Italian. The ability to dub sound had not yet been perfected, so four additional 35mm versions were shot in foreign languages, each featuring a different cast41. This was the first, and unfortunately the only time, that the Grandeur format was really used to its full advantage. Sweeping landscapes fill the screen, a wagon train nearly 200 strong begins its journey west, enemy Indians circle an encampment in the wilds, the caravan fords a river, all with views that stretch far beyond what was possible in a standard 35mm film. So impressive were the results, that The Big Trail was screened at the White House for President Herbert Hoover as part of his centennial celebration of the Oregon Trail42. The movie premiered in Grandeur to great fanfare at the Grauman’s Chinese theater in Los Angeles on October 2, 193043. It also opened in Grandeur at the Roxy in New York, but all other engagements seem to have been for the 35mm version. Fox ultimately did not achieve the financial success they had hoped for with The Big Trail, due in part to the limited number of locations a Grandeur picture was able to be shown. More than two million dollars had been spent making the film, and had Grandeur projectors and screens been installed in more cities, the reaction of moviegoers would likely have been far different. However, the film remains important today for its introduction of John Wayne to the movie watching public, its strikingly modern cinematography and sweeping panoramas of the west, and its pioneering use of sound and widescreen technologies in combination. The 70mm version of “The Big Trail” was painstakingly restored by the New York Museum of Modern Art in the 1980's by master restorers Karl Malkames and Peter Williamson from a badly shrunken original negative, and the results are very impressive even today.

A Good Idea Before Its Time

There are a number of reasons that the Grandeur system failed to catch on in the 1930’s. Money was a huge factor, as theaters would need to be outfitted with new screens and projectors in order to show a Grandeur film. Cash-strapped theater owners had just spent considerable money installing the equipment to screen sound pictures, and further converting a theater for Grandeur exhibition was expensive. Costs were high for the studios as well. While the method of capturing and reproducing sound would remain the same, production would require new cameras, new printers that could accommodate the wide film, and new processing equipment. The 70mm nitrate film itself was more difficult to work with than standard 35mm nitrate film, as it was brittle and prone to buckling and curling. Cinematographer Edeson noted, "[a] buckle in a 70 millimeter camera is a terrible thing, for it not only ruins a large quantity of valuable film, and often damages the camera, but it invariably makes the motor a total loss"44. Industry pressures also acted to stop all wide film production in its tracks. All of the major studios signed an agreement in 1930 through the Hays Office that would curb all current and future wide film development unless a single industry standard could be agreed upon45. At the same time that the Hays Pact was being negotiated, William Fox was forced to resign from his own studio and to sign over his voting interests to his opponents. Harley Clarke, Fox’s successor as studio head, agreed to stop development and production of Grandeur films, and absorb the more than two-million-dollar production cost already expended, closing the book on Grandeur. While William Fox was still the owner of the Grandeur process as well as the cameras, he no longer had the capitol or infrastructure to produce motion pictures46. It wasn’t until the 1950s that wide film and wide screen movies would make their triumphant return. It was 20th Century Fox that led the next major foray into widescreen with their Cinemascope process, used on such films as “The Robe” (1953), “The Diary of Anne Frank” (1959), “Oklahoma!” (1955), and “Forbidden Planet” (1956).

Our Thanks

We must extend our gratitude to the many people that have helped us in our research: the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the USC Cinematic Arts Library, Marilyn Ann Moss, 20th Century Fox, Tom McCutchon and the Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library, the California State Railroad Museum, Joan Miller and the Wesleyan Cinema Archives, the Arizona Historical Society, the Montana Historical Society, the Research Center of the Utah State Archives and Utah State History, the Wyoming State Archives, the New York Museum of Modern Art, the Bibliotheque Nationale de France, the Los Angeles Public Library, Michael Madden, Ralph Sargent, John Hora, Carol Grey, and Corbis Images. If you have any further information, photographs, suggestions, or corrections to our above research, we would be glad to hear from you.

Sources:

- Mitchell Camera Corporation shipping ledger. (February 24, 1964). Mitchell Camera Corporation.

- Joseph L. Kelley, "Wide Film Captures Old Broadway," Motion Picture News, (March 1, 1930): 48-9.

- Grace Kingsley, "Fox Perfects Novel Talking Device," Los Angeles Times, (February 20, 1927): C 17.

- Wikipedia contributors, "Tri-Ergon", Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 27 January 2021, View source.

- "Earl I. Sponable," obituary in SMPTE Journal, (February 1978): 96, found in the Earl I. Sponable Papers, Columbia University Rare Books and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York.

- Earl I. Sponable. "Grandeur Cameras" memo from Sponable to W.C. Michel. (June 24, 1932). Earl Sponable Collection, Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, NY.

- J.D. Elms. Lens Focusing Device. US Patent 1,447,173, filed July 23, 1921 and issued March 6, 1923.

- John D. Elms. "Demonstration and Description of the Widescope Camera," Transaction of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers 14 (1922): 124-129.

- Sponable memo to Michel.

- Sponable memo to Michel.

- "Grandeur Conference on August 10, 1928 In Courtland Smith's Apartment," Earl I. Sponable Papers, Columbia Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, Columbia University, New York.

- "New Film Projection Provides for Depth," Hamilton Daily News, (September 25, 1929).

- Sponable memo to Michel.

- Sponable memo to Michel.

- Sponable memo to Michel.

- Sponable memo to Michel.

- "Grandeur Conference on August 10, 1928 In Courtland Smith's Apartment".

- "Memo To: Mr. Sol M. Wurtzel Re: Report on Grandeur Equipment" (November 2, 1929), Earl I. Sponable Papers, Columbia Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, Columbia University, New York.

- Purchase Order #A. 4175 from Fox Case Corporation. June 17, 1929. Earl Sponable Collection, Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New York City, NY.

- Ad, "Mitchell Wide Film Cameras," American Cinematographer, (July 1930).

- Mayme Ober Park. "Wide Film Makes its Debut Auspiciously at Movie Capital," Daily Boston Globe, (March 13, 1930): 29.

- Mordaunt Hall, "Grandeur Films Thrill Audience: Rush and Roar of Niagara Are Among the Startling Effects at the Gaiety," New York Times, (September 18, 1929).

- "Theater Record Established by Follies Revue," Los Angeles Times, (June 13, 1929): A13.

- Joseph L. Kelley, "Wide Film Captures Old Broadway," Motion Picture News, (March 1, 1930): 48-9.

- Mordaunt Hall, "GRANDEUR'S FIRST REAL TALKER SHOWN; "Happy Days," William Fox's Film at the Roxy, Boasts Largest of Screens. MANY FAVORITES IN CAST Dialogue of Large Group Made Possible--Minstrel Show Imaginatively Staged.," The New York Times, (February 14, 1930).

- Edwin Schallert, "Grandeur Film Arrival Event: Outdoor Shots are the Thrill in New Medium," Los Angeles Times, (March 3, 1930).

- "Happy Days (1930)," AFI Catalog of Feature Films - The First 100 Years 1893-1993, View source.

- "Prediction Made on New Grandeur Film," Los Angeles Times, (March 5, 1930): A10.

- William Stull, A.S.C., "Seventy Millimeters: The First of the New Wide Film Processes Reaches Production," American Cinematographer, (February 1930): 9, 42-3.

- Miles Kreuger, "Song O' My Heart," www.mccormacksociety.co.uk/Mccormack/Studies/Song o%27MyHeart by Miles Kreuger.htm, 1984.

- Kreuger

- Kreuger

- Associated Press, "Snapped Famed WWII Betty Grable Pinup: Photographer Frank Powolny Dies at 84," Los Angeles Times, (January 11, 1986).

- Marquis Busby, "The End of 'The Big Trail!': One of the Greatest Location Trips in the History of Pictures is Finished," Photoplay, (October 1930): 33.

- "The Big Trail (1930)," AFI Catalog of Feature Films - The First 100 Years 1893-1993,View source.

- Frank Powolny, Photographer, "Raoul Walsh and His Pet Grandeur Camera", (Wal-26-GP59), photograph (c1930), Hollywood Museum Collection, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

- Frank Powolny, Photographer, "Something Has Gone Wrong". photograph, (Wal-26-GP85), (c1930), From Twentieth Century Fox Archive.

- Raoul Walsh, "The Log of 'The Big Trail,'" Gem Theater Talking Picture Magazine, (c1930): 5 and 7.

- Walsh.

- The Big Trail, Fox Film Corporation. July 29, 1930. advertisement. The Film Daily, 2. View source (accessed June 13, 2013).

- "The Big Trail (1930)," AFI Catalog of Feature Films - The First 100 Years 1893-1993,View source.

- "'Trail' at White House," The Film Daily, vol.54 no.6 (October 7, 1930): 8.

- Ron Miller, "Early Technology Almost Headed John Wayne's Career Off at the Pass," Chicago Tribune, (February 20, 1986): sec.5 pg.9.

- Arthur Edeson, "Wide Film Cinematography: Some Comments on 70mm Camerawork from a Practical Cinematographer," American Cinematographer, (September 1930).

- John Belton. "Grandeur: A History, 1927-1930," (paper, Rutgers University, 1990), 4.

- Belton.

Other Sources Consulted

- Muriel Babcock. Los Angeles Times, (April 13, 1930): B 11.

- Quinn Martin, "The New Films," (The World, October 25, 1930), quoted in "World's Biggest City Lauds World's Mightiest Picture in World's Biggest Theater", advertisement, Fox Film Corporation. The Film Daily, vo.54, no.24 (October 28, 1930).

- "New Cameras Will Produce Pictures of 60 Degrees Visual Angle," Motion Picture News, (June 25, 1921): 98, 104.

- J.D. Elms. Motion Picture Camera. US Patent 1,836,584, filed December 16, 1922 and issued December 15, 1931.

- J.D. Elms. Motion Picture Camera. US Patent 1,783,463, filed April 10, 1928 and issued December 2, 1930.

- Walter Blanchard, "Making 'Stills' Tell a Story . . . Frank Powolny, 'Ace' Still Man, Tells How It Is Done," American Cinematographer, (September 1930): 12-13, 26-27.

- "As The Editor Sees It - And Now Grandeur," The Motion Picture Projectionist, (October 1929): 18.

- James J. Finn, "The Grandeur System," The Motion Picture Projectionist, (October 1929): 19.

- "First Wide Film Publicly Shown is Fox's Grandeur with 'Movietone'," Motion Picture News, (September 21, 1929): 1048.

- Terry Ramsaye, "William Fox One of Fighting Greats of Film Industry," Motion Picture Herald, (May 17, 1952): 25, 28.

- "The Big Screen - Nest Development to Find Application in the Theatre: Many Companies Perfecting Methods to Photograph Scenes at Least Double the Width of Present Standard - Will Aid Realism of Talkies," Motion Picture News, (August 3, 1929): 428.

- "$67,000,000 Equipment Merger is Announced; Third Dimension Machines Are to Be Marketed - Grandeur, Inc., One of Combine, Believed to be a Fox Affiliation," Motion Picture News, (July 20, 1929): 274.