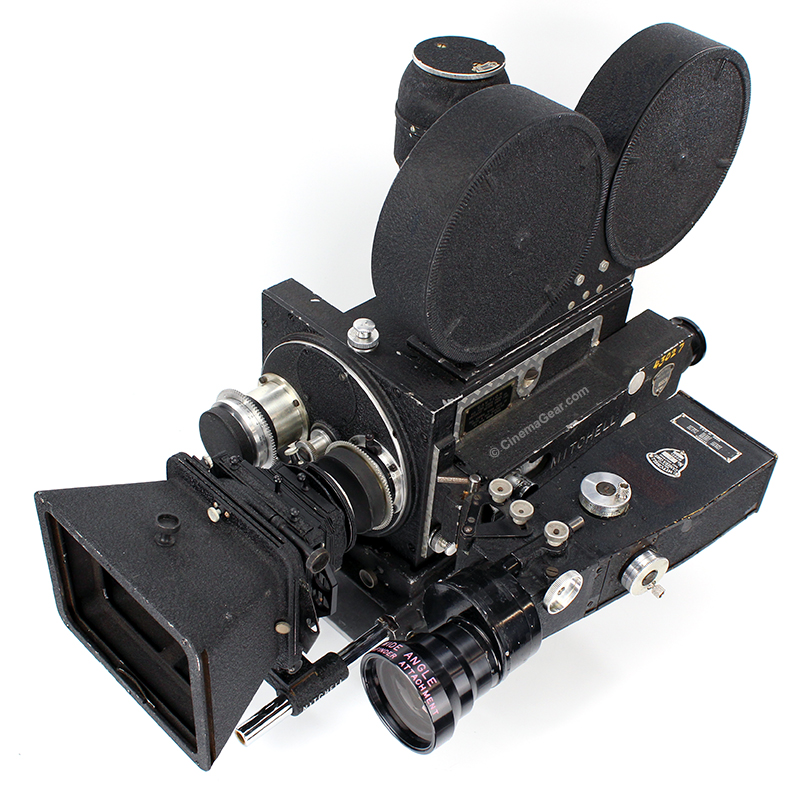

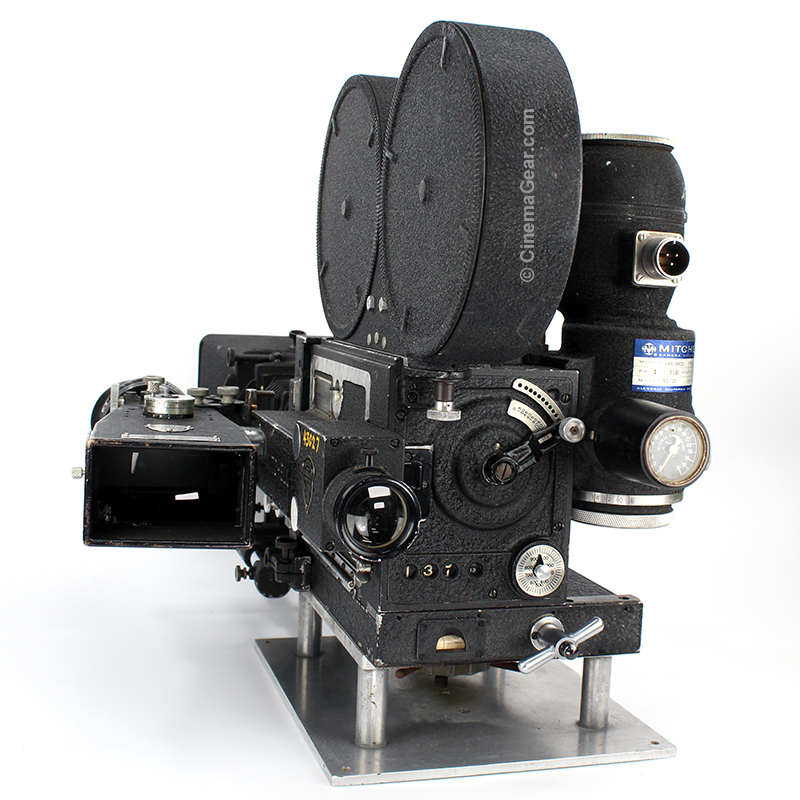

Mitchell GC #1032

$5,500

Item #C12090

Mitchell GC #1032 comes complete with a 400’ magazine, a Mitchell sidefinder, a Mitchell matte box, a peanut motor, and 3 Baltar lenses. The riser plate is shown for demonstration purposes only and is not included.

Mitchell GC #1032 was originally sold to the United States Army Aberdeen Proving Ground on August 11, 1953. Located just outside of the city of Aberdeen, Maryland, the Aberdeen Proving Ground was established by an act of Congress in 1917 as the United States prepared to enter World War I. They began testing field artillery weapons, ammunition, trench mortars, air defense guns, and railway artillery in January 1918. After the war, Aberdeen’s peacetime mission shifted to research and development.

In 1941, the Ballistic Research Laboratory was opened to conduct testing and experiments in ballistics and fire control. Aberdeen’s most important development during the World War II period was the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator, or ENIAC, the world’s first digital computer. Through the following decades, Aberdeen Proving Ground has remained a leader in research and development for the U.S. Army. Today, APG is recognized as a world leader in research, development, testing, and as an evaluation facility for military weapons and equipment, as well as supporting military and civilian scientists, engineers, technicians, and administrators.

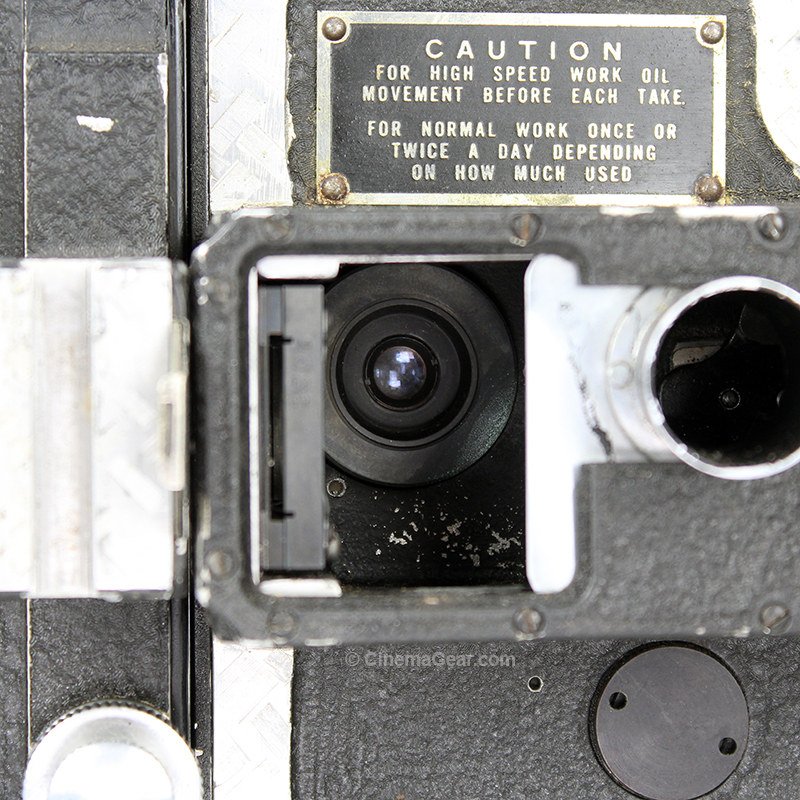

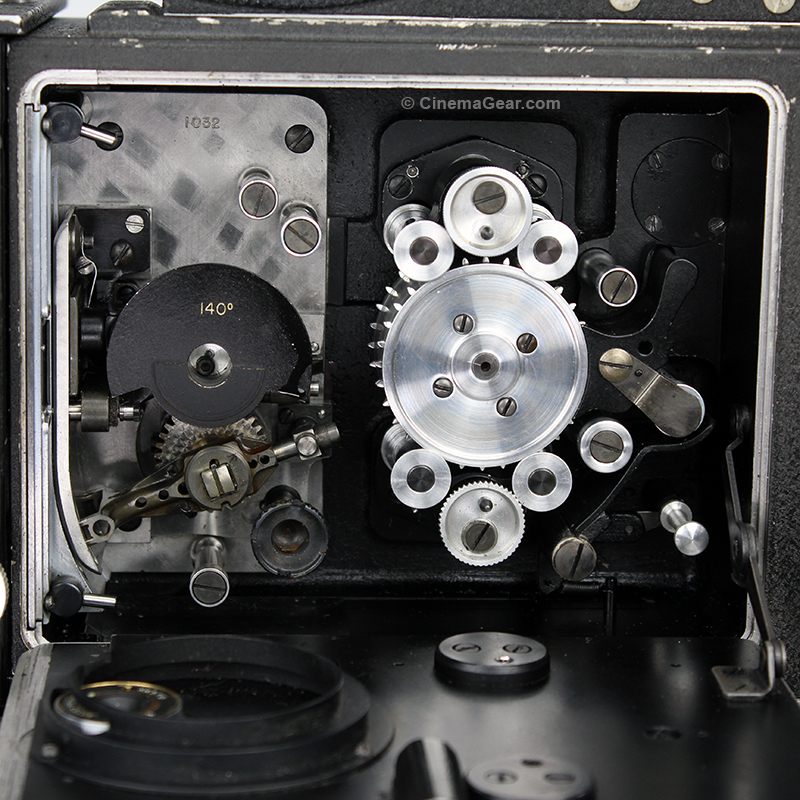

Beginning in the early 1940’s, Mitchell introduced two chronograph versions of their GC camera that incorporated more scientifically oriented instrumentation for use by the aircraft and missile industries. There are two versions of the Mitchell Chronograph, the Type A and Type B, designed in collaboration with the U.S. Navy. Both versions record an image of a clock face (or other scientific instrumentation) and the main subject on each film frame. The Type A design seen on this camera makes use of an auxiliary lens built into the camera door that focuses the chronograph image onto the film through a secondary fixed shutter on the movement to a prism mounted in the movement’s pressure plate. The clock face image is then recorded on the emulsion through the base of the film. These chronograph cameras were used mainly by the military to document testing of various weapons systems and aircraft.

Photo Gallery:

A History of the Mitchell Camera Corporation

When the Mitchell Standard hit the market in 1921, it was met with immediate praise and a flood of orders. Four years of hard work had gone into the camera’s design, and what emerged was a camera that left a lasting impact on the motion picture industry. The Mitchell Camera Corporation traces its origins back to a wooden rackover camera designed and patented by John E. Leonard. Around 1916, Leonard demonstrated his camera at Universal Studios, where they had been making a popular series of animated cartoons that featured live actors superimposed over chalk drawings. Leonard’s camera utilized his unique rackover focusing mechanism which left the taking lens stationary and moved the camera between the film plane and the viewfinder, an ideal setup for this sort of work. Universal was not interested in building their own cameras, but among those who witnessed Leonard’s demonstration was one George A. Mitchell. At the time, Mitchell was working in the Universal Photographic Department’s camera repair shop under department head John M. Nickolaus.

George Alfred Mitchell was born in Tennessee around the turn of the 20th century. Mitchell’s interest in photography began in childhood when he took his first photos with a cardboard camera. He joined the Army Signal Corps and was stationed in Alaska in 1907. In the spring of 1911, after being discharged from the Army, Mitchell moved to California where he found work as a machinist at Frese Optical Company in Los Angeles. Frese serviced and repaired surveying and drafting equipment, along with a variety of other precision instruments. By 1914, they had become one of the few locations in southern California where cinematographers could get their cameras repaired or modified, or have replacement parts machined. Mitchell’s previous experience with photography led him to become a camera technician at Frese. This acquired expertise in turn helped Mitchell get a job in the camera repair shop at Universal Studios, where he repaired and modified cameras based on cinematographer’s requests. Mitchell also found occasional work around the studio as an extra cameraman. By working in the studio repair shop and on set, Mitchell was able to see firsthand what cameramen wanted in their cameras and what improvements needed to be made to the existing equipment to make those changes happen.

When he saw Leonard’s camera demonstration in 1916, Mitchell was very impressed and, while the studio wasn’t interested in producing Leonard’s design, the two men kept in touch. The Spanish Flu epidemic hit the country, and the studios, very hard in 1918, and Mitchell was laid off from Universal as a result. Luckily, he was able to return to his previous job at Frese where he worked his way up to shop foreman. While back at Frese, Mitchell was approached by Leonard for help to build a steadier movement for his camera. Based on Leonard’s original design, Mitchell built a new movement that used stationary registration pins for increased steadiness. After installing the redesigned movement in the improved camera, Leonard used it to shoot a movie called “The Kentucky Colonel,” produced by William “Smiling Bill” Parsons of the National Film Corporation of America.

After the movie was completed, Leonard convinced Parsons to help him raise money to manufacture the camera. To that end, Parsons formed a corporation called the National Motion Picture Camera Corporation with Parsons as president and Leonard as a stockholder. A camera based on Leonard’s improved design was built by the Hunt Machine Company in Los Angeles. This camera was sold to cinematographer Homer Scott, who took it to Australia where it was sadly lost. Leonard and Parsons were still not satisfied with this version of the camera, so they once again reached out to Mitchell for help. Mitchell left his position as shop foreman at Frese to join Leonard and Parsons, and to design a new camera from scratch. Parsons was still seeking investors in their new company, and so sold a big block of stock to a group of ranchers from the Pacific Northwest. One of these investors, a Mr. Logan, was made a director of the National Motion Picture Camera Corporation, and the company rented office and machine shop space on Santa Monica Boulevard in the former Berwilla Studio.

Mitchell had barely begun work on the design of the new camera when Parsons suddenly died after a brief illness in 1919 at the age of 41. When Parsons’ estate was settled, Logan acquired all of the shares of the company. Leonard had borrowed money from Parsons in excess of the value of his stock, and so found his shares forfeit. He withdrew from the company entirely. Logan now persuaded Mitchell to keep the business going as a repair shop. This turned out to be a huge success, and not only was Logan able to recoup his investment, but Mitchell was able to resume work on his new camera.

By the Fall of 1920, Mitchell had completed a prototype of the new camera and had it ready for testing. With the help of his friend, cinematographer Charles Rosher, Mitchell was given the opportunity to use his prototype as a third camera on Mary Pickford’s film “The Love Light” (1921). Tests were successful, and Mitchell was happy with his design. Shortly after these initial tests, Logan sold his interest in the company to Harry F. Boeger, a retired lumberman, and gave Mitchell some of his stock from the Parsons estate. Mitchell’s name was on several of the company’s patents, and so in exchange for the patents, Boeger offered Mitchell a one sixth interest in the company, and made him chief designer. Boeger also changed the name of the company to the Mitchell Camera Corporation.

With corporate matters now mostly settled, it was time to offer the new camera for sale to the movie industry. Mitchell’s prototype was a huge departure from Leonard’s original design, but it did incorporate a much-refined version of the rackover mechanism that had so impressed Mitchell in Leonard’s initial demonstration. The new Mitchell Standard camera was constructed of metal rather than wood and featured a totally redesigned movement. This movement differed from Leonard’s design by using moving registration pins and pull-down claws operated by gears and cams. This made for a smoother, quieter film transport mechanism. The camera also included a built-in set of adjustable mattes, an internal floating iris behind the lens, a built-in turret disc with filter and effects mattes, and a 170-degree automatic dissolve shutter.

The first Mitchell Standard off the production line was sold to cinematographer Charles Van Enger in 1921. Charles Rosher, Tony Gaudio, and Sol Polito were among the early cameramen who adopted the new Mitchell Standard camera. Mitchell’s camera quickly gained a reputation for being steady, reliable, and user-friendly. Over time, the Standard, and the camera models that followed, came to be Hollywood’s cameras of choice for feature film, television, and commercial production.

The Mitchell GC (“Government Camera”) was adapted from the Mitchell Standard sometime in the 1930’s or 40’s as a more economical model designed originally for the United States military. Features such as the built-in variable effects mattes and the floating iris were eliminated, and a more industrial finish was used on the movement and other precision parts. Later in the development cycle, two chronograph models were added to the GC line. The chronograph cameras incorporated more scientifically oriented instrumentation for the aircraft and missile industries, as well as other military applications. Both the stock GC and the chronograph models formed the backbone of U.S. military’s camera inventory. The Mitchell GC remained a core part of Mitchell’s product line through the 1970’s.

Sources:

- Robert V. Kerns, "The Mitchell Camera Story," American Cinematographer, (April 1968): 272-4, 296-301.

- Charles Loring, "The Mitchell: Hollywood's favorite studio camera," American Cinematographer, (March 1959): 174-5, 194-7.

- Charles Loring, "The Mitchell: Part II," American Cinematographer, (May 1959): 294-5, 312-14.

- "National Film Capitalized at $100,000," Motion Picture News, (May 29, 1915): 65.

- "National Film Corporation Scene of Great Activity," The Moving Picture World, (October 4, 1919): 138.

- Ira B. Hoke, "Mitchell Camera Nears Majority," American Cinematographer, (December 1938): 495-6, 522-3.

- Arthur Frese, telegram to Anderson Land & Loan Co., January 7, 1913.

- Sol Polito, "The BNC Mitchell Silent Camera," International Photographer, (May 1939): 6-9.

- "Mitchell Blimp", American Cinematographer, (February 1949): 69.

- "Photography in Rocket Tests," Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, (February 1950): 145.

- Joseph V. Mascelli, "Mitchell Introduces New 35mm Reflex Camera," American Cinematographer, (June 1960): 360, 371-3.

- "Mitchell R-35 Reflex," ad in American Cinematographer, (July 1960): 389.

- Joseph Henry, "The Mitchell Mark II Reflex," American Cinematographer, (January 1963): 36-7, 52.

- Handbook Operation and Service Instructions: 35mm High Speed Chronograph Motion Picture Cameras Types "A" and "B", Published under authority of the Secretary of the Air Force and the Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, revised (February 1, 1958).

- J.E. Leonard. Film Moving Mechanism for Motion Picture Cameras. US Patent 1,390,247, filed March 30, 1920, and issued September 6, 1921.

- J.E. Leonard. Adjustable Iris for Cameras. US Patent 1,392,876, filed November 1, 1919 and issued October 4, 1921.

- J.E. Leonard. Adjustable Iris and Curtain for Cameras. US Patent 1,396,717, filed December 4, 1919 and issued November 8, 1921.

- George A. Mitchell. Kinetograph Movement. US Patent 1,403,339, filed May 12, 1920 and issued January 10, 1922.

- George A. Mitchell. Viewing Device for Cameras. US Patent 1,646,829, filed July 16, 1925 and issued October 25, 1927.

- George A. Mitchell. Movement Mechanism for Cameras and the Like. US Patent 1,648,559, filed December 7, 1925 and issued November 8 1927.

- George A. Mitchell. Dissolving Shutter. US Patent 1,812,056, filed August 10, 1929 and issued June 30, 1931.

- George A. Mitchell. Film Movement. US Patent 1,850,411, filed April 25, 1930 and issued March 22, 1932.

- George A. Mitchell. Film Movement. US Patent 1,851,400, filed April 25, 1930 and issued March 29, 1932.

- George A. Mitchell. Film Movement. US Patent 1,912,535, filed April 25, 1930 and issued June 6, 1933.

- George A. Mitchell and Edmund Lindgren. Kinetograph Movement. US Patent 1,954,885, filed August 7, 1929 and issued April 17, 1934.

- George A. Mitchell. Camera Focusing Mechanism. US Patent 2,000,090, filed February 23, 1934 and issued May 7, 1935.

- George A. Mitchell. Operating Means for Four-way View Mats. US Patent 2,058,813, filed October 16, 1933 and issued October 27, 1936.

- George A. Mitchell. View Finder Parallax and Photographic Lens Focusing Mechanism for Motion Picture Cameras. US Patent 2,012,515, filed March 16, 1934 and issued August 27, 1935.

- George A. Mitchell. Sound Insulated Motion Picture Camera. US Patent 2,088,714, filed May 7, 1934 and issued August 3, 1937.

- George A. Mitchell. Shutter Dissolve Mechanism. US Patent 2,088,715, filed May 7, 1934 and issued August 3, 1937.